They’re useful and they’re everywhere – but could overusing them bring us unintended consequences?

I’m a bit of a latecomer to Netflix. I only got hooked about a year ago.

And as I surfed from one entertainment offering to another, I discovered Netflix’s most nifty feature: subtitles.

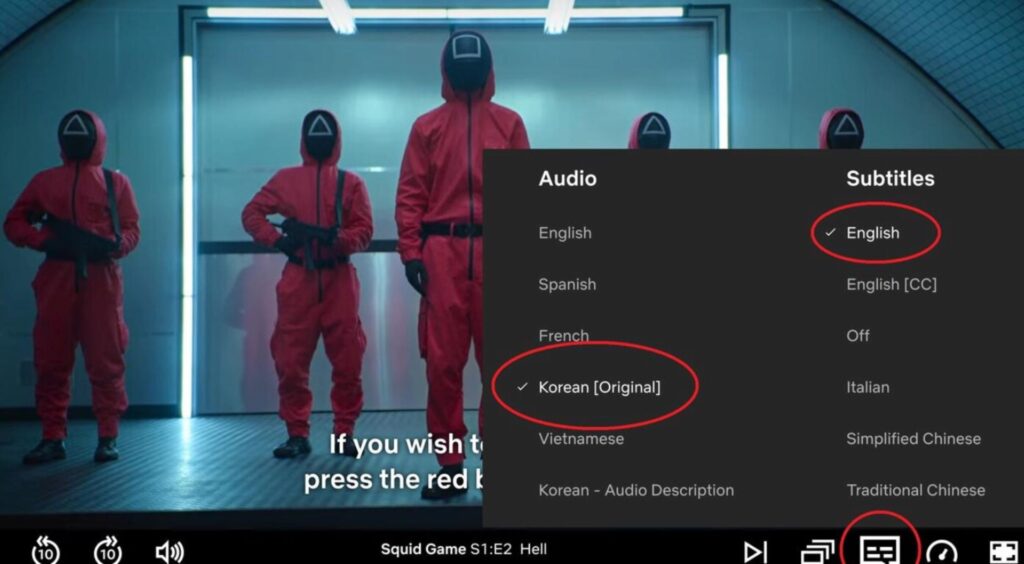

Those little white words at the bottom of the screen come in quite handy, particularly with all the cross-cultural and foreign language content. They helped me decipher the confusing diction of 18th century Scottish highlanders through 7 seasons of Outlander. They navigated the quirky Norwegian dialect in Netflix’s first original series from 2012, Lilyhammer (was Steven Van Zandt’s mobster Frank Tagliano really the proprietor of the Bada Bing himself, Silvio Dante?). When I binge-watched all of Squid Game one weekend I alternated between subtitles and English dubbing over the original Korean. (I’d advise against doing this show in one sitting. You won’t be right for days.) And once I finally got around to Breaking Bad, I simply kept them on. As Jesse Pinkman might say: Subtitles, YO!

Dinna Fash, Sassenach — I ken that no one understands my Scottish Gaelic. We’ll go through the stones of Craigh Na Dun to 2023 and fix the subtitles…

I’ve read that many people rely heavily on subtitles because they find the dialogue often sounds muddled and difficult to understand. This reportedly has to do with how post-produced audio is mixed down and delivered over streaming services. The full technical explanation starts to get complicated, but the quick and dirty of it is that audio over streaming media is produced to different standards from traditional broadcast TV and film. Some insist it results in a substandard, degraded sound quality, especially when trying to distinguish human conversation from other elements like background music or sound effects. Despite various fixes and hacks, some complain that it still sucks.

Subtitles, however, aren’t used solely to overcome audio problems.

I was surprised to learn that a recent survey shows 50% of Americans watch content with the subtitles on most of the time. The numbers spike even higher by generation: 53% of millennials use them, and a whopping 70% of Gen Z.

57% of people watch content when they’re out in public. I can’t imagine doing this myself, but it appears I’m in the minority. Again, it’s more pronounced among young people – 74% of Gen Z.

Those surveyed say subtitles serve a practical purpose while viewing on a device in a public space: sensitive to disturbing others, they turn down the volume; interestingly, the same is true in the privacy of their homes, because similarly they don’t want to annoy roommates or family members.

Yet this goes beyond simply being polite. It seems there may be a cultural shift afoot.

Again, it’s the younger generations driving the trend. Unlike the baby boomers or Gen X, for some millennials and all of Gen Z subtitles have always been there. To this entire segment of the population that grew up with Facebook and TikTok, subtitles are not only commonplace, but frankly an expectation. Whether the sound is turned on or off, it’s understood that you’re supposed to see words on screen to accompany whatever you’re watching. That’s just how it works – it would be strange not to see them.

This all got me thinking, particularly in light of another statistic I recently spotted. It says millennials (those born between 1981 and 1996) will make up 75% of the workforce by the year 2025. That’s not far away, as of this writing. That means those born 1997 and later are not far behind!

Clearly the media consumption habits of this younger set have massive implications for any of us working in media production – not just entertainment, but I think also the “non-broadcast” realms that spill into areas such as business and educational content. As these upcoming generations displace older adults, their new-fangled quirks will quickly become the norm. A 22-year-old Gen Z kid comes with a vastly different perspective from a 57-year-old Gen Xer, and content producers will need to get wise to that.

Consider subtitles. For Gen X, demanding these kinds of visual cues wasn’t a thing. Not for movies, not for TV. Certainly not for marketing videos or e-learning modules. The deal was you listened hard and focused on what you heard. You paid attention and adapted to the audio. It was pretty much all you had.

For Gen Z? No way. You’d better have words on that screen. And by the way, they’re likely killing the sound.

Let’s take this to one possible logical conclusion. Does this mean that audio eventually becomes optional? Irrelevant? Obsolete? Will we collectively begin to lose an appreciation for that wonderfully immersive sensory experience of sound? Will people cease to care about music, narration, sound effects and the emotional richness they create?

I hope not. I can’t envision a world in which people would be happy only with images and words whipping across a screen. I suspect there will always be a desire for “ear candy.”

There’s a more practical concern. When you lean on subtitles and stop actively listening, you miss out on all the layers of nuance, context, attitude and information that sound can convey. Voice and narration in particular – inflections, pauses, emphasis, tonality, emotionality and other unique signals get stripped away. It corrodes and cheapens our ability to communicate with one another effectively and fully, and becomes a very shallow, one-dimensional exercise, empty of humanity and meaning.

This may put me at odds with younger folks, but I’ll say it:

It all feels very Tik-Tokky. And that’s not a good thing.